|

|

|

This article is from June 1995 Shotgun Sports and is reprinted courtesy of Shotgun Sports Magazine. Shotgun Sports can be found online at www.shotgunsportsmagazine.com. |

By David A.B. Price

Gun fit has long been denied the importance it should be accorded by shotgunners in the United States. The reason is fairly simple: When a person lifts a gun out of the rack and brings it up to his or her face, he or she will usually push and cram the cheek down on the stock and cant the eye over the rib to make the "sight picture" just what it should be — straight down the rib's middle and flat on or just a bit above it. They'll twist and bend like pretzels to line up the rib correctly, especially it it's a gun they really fancy for its figured wood, intricate engraving, bargain price or whatever reason the potential buyer happily imagines.

|

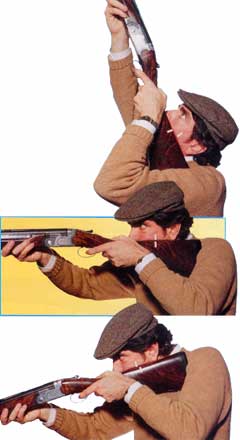

| Top: Here the shot is being taken at a high, incoming bird. As the shooter's weight shifts backward, his shoulder rises slightly behind the gun and his cheek is shifted backward along the comb.

Center: This photograph shows the shot being taken at a head-high crossing bird. Note tape marks where the shooter's cheek contacts the comb of the stock. Bottom: This photograph shows the shot being taken at a rabbit. Notice how the shooter's cheek has moved forward on the comb as his weight is shifted forward. |

It is easy to convince yourself a gun fits "well enough" if you are predisposed to like the gun and want it badly. Even if a gun does appear superficially to fit, the fact is most people don't swing a gun up to their face in the field the way they deliberately mount a gun when first examining it in the store. While this is not quite so meaningful for those who intend to shoot the "gunup" disciplines (trap and skeet), it can mean an awful lot to those who shoot live birds and the rapidly increasing numbers of shooters who are shooting Sporting Clays from a gun-down position and having a bit of trouble hitting very much.

|

The parallel comb can be an all-around stock for the low-gun sports. |

For years, American bird shooters have not been too concerned about gun fit. After all, they do shoot a few each time they go out in the field or marsh, and if they don't, well, the birds were just too fast or "jinky" or whatever. It just wasn't their day to hit them. God never intended for a man to hit everything he pointed his gun at.

Trap and skeet shooters essentially bang away at the same targets time after time and eventually learn how to position themselves over the gun consistently for each type of shot. They learn the characteristics of their guns, or more accurately, they learn their guns' fit characteristics and adapt to the fact that the gun shoots high or low, left or right.

This acceptance of a less-than-correct fit is perfectly all right if the gun is mounted the same way every time and the barrel alignment is able to be visually checked by looking over the rib before calling for the bird. If, however, one is in the field or shooting one of the unpredictable clay-target games, such as Sporting Clays, where the gun is not premounted, the gun must properly fit the shooter. If not, he or she rarely will be able to hit targets with any sort of consistency, to the point where it may drive him or her to give up any random-target, gun-down type of shooting in utter frustration. Hunters, as previously noted, often simply do not expect to hit much, and thus claim their real satisfaction comes from working the dogs and getting out in the fresh air as much as from actually shooting birds. This is a lie: The greatest satisfaction in shooting is hitting what the gun is pointed at, and no one who really shoots will allege otherwise.

Basic gun fit involves shaping, bending or adding material to the buttstock of the shotgun until the gun "comes up" from a low hold position so the shooter's face is correctly positioned on it.

Movement to the face from the down position should be smooth and involve no conscious thought on the part of the shooter. It should be done exactly as if the shooter were swinging onto a moving target. You should not look at the gun. After the gun is mounted and the swing stopped, you can look down along the rib to see if you are positioned correctly: You should be right down the middle of the rib and just a bit high on it, depending on how much above the gun you like to see your targets. The more rib you see, of course, the higher the gun will shoot. If the sight picture is wrong, the gun needs to be fitted.

|

|

To achieve proper gun fit, many points must be considered. Length-of-pull, for one, influences cheek to trigger-finger-hand relationship, sight picture, grip position on the forearm and ease of shouldering. Then there are drop at comb, pitch and cost to consider. |

|

The basic gun stock measurements are the drop (in inches, usually) perpendicular from the extended line of the gun's top rib down to the comb of the stock and down from the line of the rib to the heel of the stock. Typical combdrop measurements are from 1 3/8" to 1 3/4". Drop at heel can run from 2" to 2 3/4". The steeper the angle of the drop from the comb to the heel, the more the shooter's shoulder and face will feel the effects of recoil. The gun will tend to jump up and back when fired, driving the stock top into the cheek of the shooter. A difference in drop from comb to heel of much more than 1" can result in a bit of a battering after a day's shooting.

Guns of the nineteenth century, especially in America, often had "crooked" stocks. The stocks had drop differentials of as much as 4". Shooters then adapted very upright shooting stances, probably because they were wearing stiff collars and ties. Also, they were shooting much gentler-recoiling black powder in their shotshells. After the introduction of nitro powders, stocks straightened out a good bit.

Length-of-pull, the measurement from the middle of the trigger to the middle of the back of the recoil pad, is the next important measurement. Depending on the length of one's arms, this measurement can be 13" to 15 1/2" or so. The important thing is that the stock is not so long as to hang the butt up in your clothing when mounting. The stock should be long enough so the knuckle of the thumb on your trigger hand does not touch your face when the gun is mounted. Recoil can cause this knuckle to whack your face.

"Cast" is the term used to describe bending the buttstock a little to the left or right to bring the shooter's eye directly in line down the center of the rib. It is possibly the most important measurement of all, because very few people have a shoulder pocket (the area where the buttstock is held against the body between the chest and shoulder) that lines up directly beneath their eye. If the barrel and stock of the gun are in an absolutely straight line when the head is brought down on the stock as the gun is mounted (as in a gun with no cast), the master eye will see just a little down the side of the barrels - the left side if you are right-handed; the right side if you are left-handed. "Cast-off" is the term used for bending the stock a little to the right (1/8" to as much as 1/2") for a right handed shooter; "cast-on" bends the stock to the left. Almost everyone can use some cast to the stock. Otherwise, the shooter will have to cant his or her head slightly over the top of the stock to get the eye down the middle of the rib. If you shoot from a gun-up stance, you can line up the eye on the rib for each shot. However, shooting from the lowgun position with a gun that has no cast, you will find the eye will only rarely align correctly down the rib.

|

|

Gun fit is extremely important when you're in the field. If it doesn't fit well in the summer, no way will you perform up to expectations with all your winter duds on. |

This is especially so as the gun is brought quickly to the shoulder at the same time the head and body are turning and following the target. If the gun is correctly cast, the gun barrel and rib will always come up to the right place under the eye. Otherwise, one will shoot a little bit more to one side or the other of the birds or clays. You can test a gun's cast on incoming overhead shots: If the gun isn't cast correctly, the shot will go to the side of the bird even though the shooter was positive the muzzle in his peripheral vision just pulled up and blotted out the bird perfectly.

As we have discussed, most guns have comb and heel-drop measurements of about 1 1/2" and 2 1/4", respectively, give or take 1/4". On almost every off-the-rack gun, the heel may be lower than the drop at the comb. In other words, the top edge of the buttstock slopes downward from the comb to the heel. The steeper the slope, the more severe will be the effects of felt recoil to the shooter. If the slope could be reduced, the barrels, breech and buttstock would be brought more into a straight line and the force of the recoil would be sent more into the mass of the shoulder and less upward into the facial area.

If you were to measure the point at which the shooter's cheek actually contacts the buttstock the drop at cheek, or face - you would find the measurement is generally in the area of 1" to 1 7/8". It is this measurement that actually indicates where the head is positioned on the stock. If this drop measurement were to be used at the comb, the face and the heel, you would have a buttstock whose top edge was all the same drop a "parallel" comb.

Such a fitting would have some distinct advantages. Recoil, obviously, would be substantially reduced, as the slope of the comb is eliminated. The gun would no longer pivot upward from recoil. A parallel comb would also ensure that the head and eye were always correctly positioned on the stock in relation to the rib. Sometimes your head "creeps" forward or backward on the stock, especially when the gun is mounted very quickly, as it generally is in the field. An enormous number of shots are missed due to incorrect positioning of the head on the stock. The master eye can be as much as " higher or lower relative to the rib if the head is just a little bit ahead or behind the optimum drop at face for the shooter. This could move the point-of-impact of the shot 6" or so up or down on a long shot. While 6" is not much, it is certainly enough to make your gun shoot where you do not think it is shooting. With a parallel comb, the eye will be at the right height above the rib every time, no matter where the shooter's head hits the stock.

|

|

One sure way to make a gun fit is with an adjustable stock. This stock has an adjustable comb and adjustable length-of-pull and is adjustable for pitch, cant and cast-off. It'll take time, but with patience you'll find the dimensions that fit you like a glove. |

|

|

Talk about critical fit - every woman shooter needs expert advice from someone who really knows what good gun fit means. Same holds true for younger shooters. You can have the best of the best and all the bells and whistles on your gun - but if it doesn't fit, you'll never shoot it well. |

In Sporting Clays one has the greatest variety of shot situations of any of the shooting games, even more so than in field shooting itself. Most shotgunners have noticed the head seems to be positioned differently on the gun for a long, high, quartering-away shot than for a low, close, crossing rabbit. As the target crosses or rises at heights above the shoulder, the shooter's face tends to creep slightly farther back on the stock as the shooter's weight moves back. For direct overhead shots, the face moves well back towards the heel. On low shots, like rabbit and grouse and shots taken down into a valley, the shooter's weight moves substantially forward over the front foot and the face tends to be pushed forward on the stock (see photos on page 23.) Depending on the type of shot, the head can move as much as 1 1/2" forward or back on the stock. With a sloping comb, the movement of the contact point of the face on the stock forward or backward can throw the shot quite high or low. With a parallel comb, this fore and aft movement of the head on the stock will not affect the position of the master eye over the rib.

While the concept of a parallel comb stock has some similarities to the Monte Carlo stock, there are significant differences. The Monte Carlo, which is parallel for most of its length, then drops down sharply at the heel, is designed specifically to be a very highshooting stock for live-pigeon shooting and trap. The parallel comb described here is meant to serve as a complete, all-around stock which can help minimize mounting errors from the low gun position, reduce felt recoil and maintain proper alignment of the master eye over the rib even if the shot taken is at a stratospherically high pheasant or ground-hugging, rocket-ship rabbit.